A tale of two grandfathers—one stuck in comfort, the other chasing tomorrow—explains why some brains stalled and others sprinted.

Every animal alive—from worms to whales—gets smarter the same way. They stumble into something that works, like dodging a hawk or cracking a nut, and do it again. And again. After thousands of years, maybe millions, that trick sinks deep, no thinking needed—just instinct kicking in. Scientists might call it moving from extelligence, stuff you learn outside, to intelligence, baked into your bones. All creatures do it. The best survive; the rest get eaten.

But us humans? We’re the oddballs. We didn’t wait eons. We turned the game upside down with one trick: imagination. No other animal, not even our cousins the chimps or bonobos, can sit there dreaming up “what ifs.” They react—bam!—to whatever’s in front of them, running drills carved into their brains over ages. We started that way too, millions of years ago, scrabbling alongside rats and starfish. Then we broke free.

How? We chose to grow smarter. Picture it: my great-grandfather teaches my granddad to spear a fish just so. Granddad drills my dad ‘til it’s automatic—stab, twist, pull. By the time I’m learning, I barely need telling. My kids roll their eyes—“Duh, Dad, we’ve got it.” My grandkids? They shrug, “Always knew that.” What started as a lesson, something we had to figure out, slides from outside know-how to inside reflex. That’s our edge—we shrink centuries into generations.

It didn’t come free. Way back, as I wrote in The Greatest Show on Earth, we apes split off, leaving the nest to wrestle with fire and wild lands. For six million years, we crept along Africa’s coasts, more beast than brain. Then imagination sparked. Each step away from that cradle—into forests, savannahs, and new dangers—forced us to think harder, adapt faster. We turned lessons into habits: hunt better, share stories, build shelters. The unsuccessful died off. Survivors stacked knowledge brick on knowledge brick, sharpening our 4 Ps—the women producing and parenting, and the men handling the servicing—providing and protecting.

Then we hit a wall. In Africa’s sweet spot, life got comfy. Food was plenty, threats were few. Why push? Our ancestors there settled in, handling the basics with ease. Intelligence stalled—no need to grow it when you’re killing it. But for those who had trekked north into Eurasia’s brutal unknown—icy winds, lean winters, unpredictable summers, predators with no mercy—it didn’t stop. No comfort there. It was sink or swim, think or die.

Those wanderers enrolled in a crash course I call the Great Eurasian University. Day and night, they faced tests: tame a wolf, trap a deer, outsmart the cold. Every win got filed away—first as a hard-earned trick, then as second nature for their kids. Over generations, it wove into their culture, their bones. While African kin lounged by the fire, Eurasians doubled their smarts, then doubled them again. Solving one problem just opened the next door.

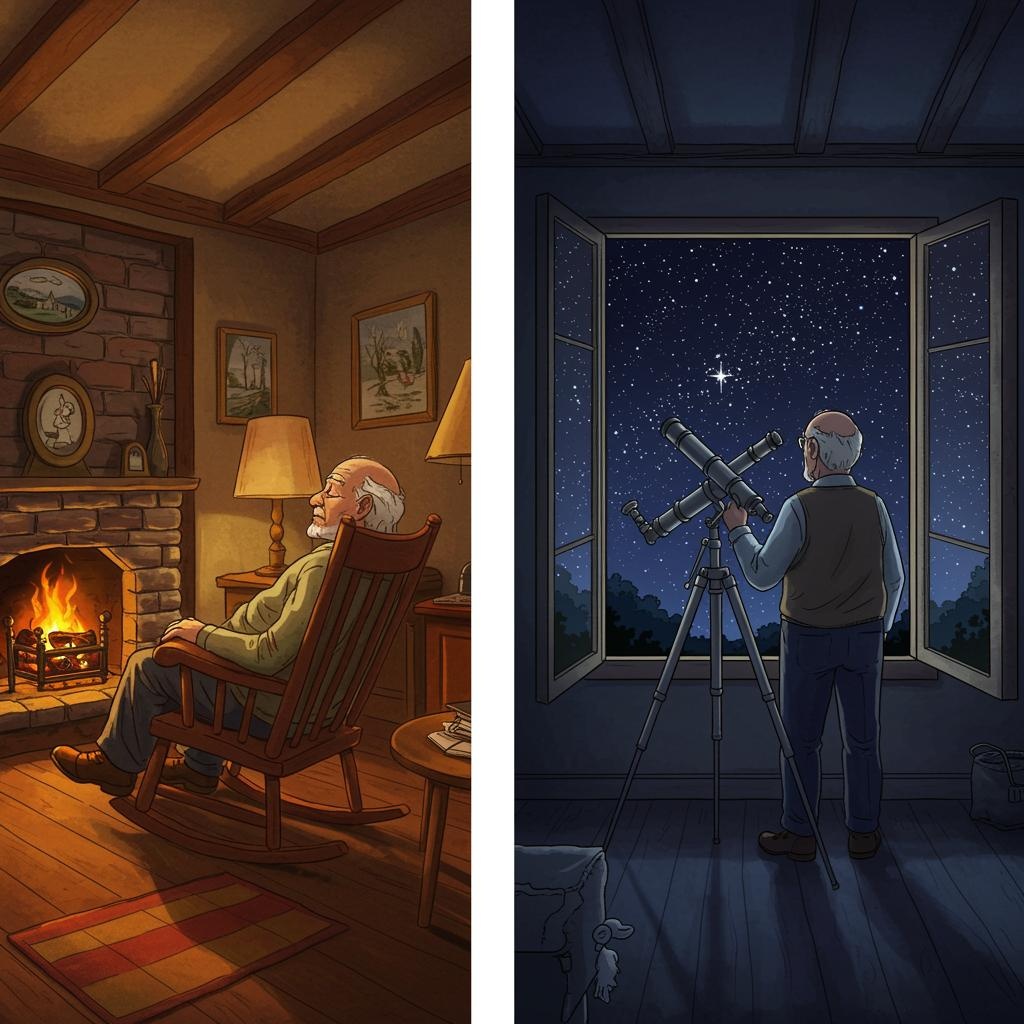

By the 1800s, you could see the split clear as day. An African grandfather peered over his cookfire, watching his grandson poke sticks in the dirt. He grinned, “Chip off the old block,” and patted himself proud. Across the sea, an Eurasian granddad sipped wine under chandeliers, eyeing his polished grandson glide through a dance. “Is he even mine?” he mused, half-amazed. One rested on yesterday; the other raced toward tomorrow.

That’s the tale, kids. Animals grind smarts out slow—success or bust. We humans hacked the system, chose to grow it fast. In Africa, we stalled in comfort. In Eurasia, we thrived on challenge. Same spark, different paths. You’ve got that choice too: stack your bricks or let ‘em crumble.

Leave a comment